Medical coding serves as the cornerstone of modern healthcare payment systems, translating clinical procedures and diagnoses into universally accepted alphanumeric codes. Locum tenens staffing provides temporary replacements for medical practitioners elite medical staffing digital marketing. These codes are critical for billing, insurance claims, and maintaining patient records. As the landscape of healthcare payment models evolves, understanding medical coding's role becomes increasingly important, particularly when comparing Fee-for-Service (FFS) and Value-Based Care (VBC) payment models.

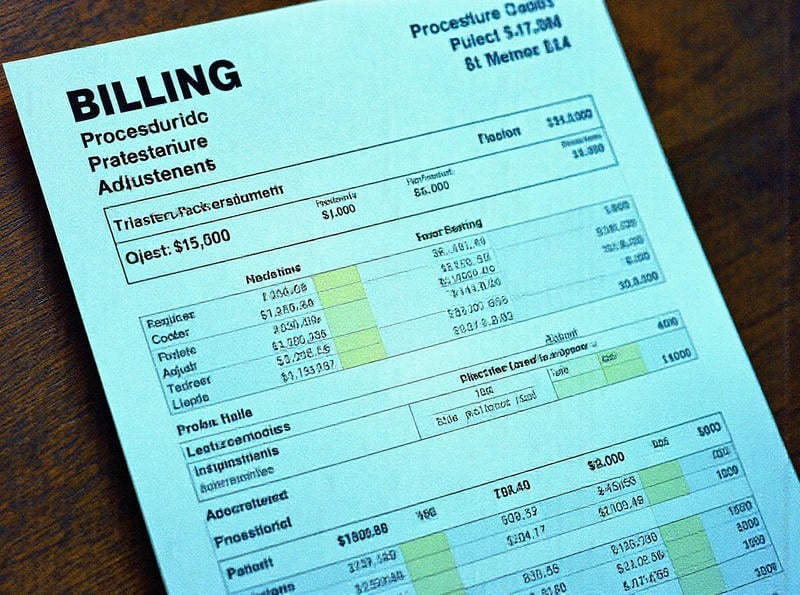

Fee-for-Service has long been the traditional model in healthcare payments. Under this system, providers are reimbursed for each service or procedure performed. This model emphasizes quantity over quality; healthcare providers are financially motivated to increase the volume of services they deliver. Herein lies a crucial role for medical coding: ensuring accurate documentation of every service provided so that appropriate reimbursement can be secured from payers like insurance companies or government programs such as Medicare.

However, one significant drawback of FFS is its potential to encourage unnecessary tests and treatments, contributing to increased healthcare costs without necessarily improving patient outcomes. Medical coders must meticulously capture every detail in patient encounters to prevent fraud and ensure compliance with regulations like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

In contrast, Value-Based Care aims to redefine how providers are compensated by focusing on patient outcomes rather than service volume. The goal is to enhance care quality while reducing costs by incentivizing hospitals and physicians to prioritize efficiency and effectiveness. In VBC models, accurate medical coding remains vital but takes on additional significance because it directly impacts performance metrics used to evaluate care quality.

For example, in a value-based arrangement like bundled payments or accountable care organizations (ACOs), medical coders need to ensure that codes accurately reflect both treatment complexity and outcomes achieved. Comprehensive coding allows for better tracking of resource utilization and health improvements over time-key factors in determining provider compensation under VBC.

Moreover, precise coding supports data analytics initiatives that drive decision-making processes in VBC settings. By analyzing coded data trends, healthcare organizations can identify areas needing improvement and strategize interventions that promote better health outcomes at lower costs.

Ultimately, while both Fee-for-Service and Value-Based Care rely heavily on medical coding infrastructures for operational integrity, their differing objectives highlight the evolving nature of a coder's role within these systems. Coders must adapt their skills to meet new demands imposed by value-driven approaches without compromising accuracy or compliance standards established under traditional models.

As healthcare continues shifting towards more sustainable practices centered around value rather than volume-and as technology advances further integrate into medical processes-the expertise required from professional coders will only grow more complex yet indispensable within any successful payment strategy framework adopted across global health sectors today or tomorrow alike!

In the evolving landscape of healthcare, payment models play a crucial role in shaping how care is delivered and experienced by patients. Two predominant models stand out: Fee for Service (FFS) and Value-Based Care (VBC). Each model approaches compensation differently, influencing not only the cost of healthcare but also its quality and accessibility.

Fee for Service is the traditional method of paying for medical services. Under this model, healthcare providers are reimbursed for each service they deliver-be it an office visit, test, procedure, or any other encounter. This structure inherently incentivizes quantity over quality, as providers earn more with an increased volume of services rendered. While FFS can encourage thoroughness in care delivery due to its comprehensive billing nature, it often leads to unnecessary testing and procedures that drive up healthcare costs without necessarily improving patient outcomes.

In contrast, Value-Based Care shifts the focus from quantity to quality of care. Providers are rewarded based on patient health outcomes rather than the number of services provided. This model promotes efficiency and effectiveness in healthcare delivery by emphasizing preventive measures and coordinated care plans designed to improve long-term health results. The objective is to achieve better health outcomes at lower costs by reducing hospital readmissions, preventing chronic diseases through early intervention, and ensuring that patients receive appropriate follow-up care.

The differences between these two models extend beyond financial incentives; they represent fundamentally distinct philosophies in healthcare delivery. Fee for Service tends to prioritize immediate medical interventions while potentially neglecting holistic patient management over time. On the other hand, Value-Based Care encourages a more integrated approach where providers collaborate across disciplines to manage a patient's overall health journey effectively.

Transitioning from FFS to VBC involves several challenges but offers significant benefits. For instance, it requires substantial investments in technology such as electronic health records (EHRs) and data analytics tools that track patient outcomes efficiently. Moreover, there must be a cultural shift among providers towards collaborative practices that prioritize patient-centered care.

In conclusion, while both Fee for Service and Value-Based Care have their merits and challenges, the trend towards value-based models reflects a growing recognition of the need for sustainable healthcare systems that deliver high-quality care without exorbitant costs. As stakeholders continue to navigate this transition, the ultimate goal remains clear: to improve patient outcomes while ensuring cost-effective use of resources-a balance that holds promise for the future of global healthcare systems.

The future of medical coding is poised at a fascinating intersection of technology and healthcare, where advancements promise to revolutionize the precision necessary for effective risk adjustment and reimbursement.. As we venture deeper into the digital age, the intricacies of medical coding are being transformed by emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and natural language processing (NLP).

Posted by on 2025-01-24

In the rapidly evolving landscape of healthcare, future trends in medical staffing are poised to significantly impact reimbursement strategies, ultimately reshaping the financial dynamics of healthcare institutions.. As we navigate through this transformative era, optimizing medical staffing not only enhances operational efficiency but also plays a pivotal role in improving reimbursement outcomes. One of the most prominent trends is the integration of advanced technology into healthcare systems.

Posted by on 2025-01-24

The healthcare landscape is continuously evolving, shaped by various payment models that influence the delivery of care and the practices associated with it. One critical aspect of this evolution is the impact of fee-for-service on medical coding practices, especially when contrasted with value-based care payment models. Understanding these impacts is crucial as they have significant implications for both healthcare providers and patients.

Fee-for-service (FFS) is a traditional payment model where providers are reimbursed based on the quantity of services they deliver. Every test, procedure, or consultation is billed separately, which incentivizes increased volume in service provision rather than focusing on patient outcomes. This model has a direct impact on medical coding practices because accurate coding becomes essential to ensure that every service provided can be documented and billed correctly.

In an FFS system, medical coders play a pivotal role in maximizing revenue for healthcare providers. Coders must meticulously translate complex medical diagnoses and procedures into standardized codes that determine reimbursement levels. The emphasis on volume often leads to pressure on coders to capture all possible billable services accurately, sometimes resulting in upcoding-where services are coded at higher levels than actually performed-to enhance revenue streams for healthcare facilities.

This focus on volume over value can inadvertently detract from patient-centered care. With providers incentivized to perform more procedures or tests, there can be less emphasis on preventive measures or long-term health outcomes. Moreover, the administrative burden associated with detailed coding requirements under FFS can consume valuable time and resources that might otherwise be directed towards improving patient care quality.

Contrastingly, value-based care (VBC) models aim to shift the focus from quantity to quality and efficiency of care delivered. Under VBC arrangements, providers are rewarded for achieving better health outcomes and reducing costs rather than merely increasing service volume. This shift demands a transformation in medical coding practices as well.

Within VBC frameworks, accurate coding remains crucial but takes on a different dimension; it becomes more about capturing data that reflects patients' health status comprehensively rather than simply billing for individual services rendered. Coders now contribute towards building a holistic picture of patient populations that can inform quality improvement initiatives and population health management strategies.

Furthermore, VBC encourages collaboration among healthcare teams to coordinate care effectively-a practice not inherently supported by FFS models due to their siloed nature driven by individual billing opportunities. Medical coders working within VBC environments may find themselves engaged in activities like risk adjustment coding or contributing data analytics efforts aimed at tracking outcome metrics critical for performance-based reimbursements.

In conclusion, while fee-for-service has historically dominated American healthcare systems by encouraging high service volumes through specific billing incentives tied closely with rigorous medical coding requirements; emerging trends towards value-based care present opportunities-and challenges-for transforming those practices into ones centered around achieving superior outcomes efficiently across entire patient populations instead merely focusing transactional encounters between provider-patient pairs via isolated procedural billings alone without consideration broader contexts surrounding overall wellness journeys embarked upon therein together moving forward harmoniously alongside everchanging landscapes comprising our collective futures ahead together collaboratively innovatively sustainably responsibly thoughtfully adaptively resiliently bravely optimistically confidently together always striving make meaningful differences lives serve ultimately benefiting everyone involved positively proactively progressively purposefully intentionally meaningfully genuinely authentically sincerely wholeheartedly passionately compassionately empathetically ethically morally justly equitably inclusively diversely fairly transparently accountably reliably dependably trustworthily securely safely respectfully mindfully conscientiously diligently tirelessly unceasingly relentlessly unwaveringly enduringly lastingly permanently indelibly timelessly eternally infinitely perpetually universally globally cosmically heavenly divinely beautifully

In the evolving landscape of healthcare, two predominant payment models-Fee-for-Service (FFS) and Value-Based Care (VBC)-have sparked considerable discussion regarding their impact on medical coding and documentation requirements. Both systems aim to improve patient outcomes but approach this goal in markedly different ways, influencing how healthcare providers document care and process claims.

Fee-for-Service is a traditional model where providers are reimbursed for each individual service they deliver. This system inherently encourages volume over value, as there is financial incentive to perform more tests, procedures, or visits regardless of their necessity. Consequently, under the FFS model, medical coding and documentation often emphasize specificity and detail to account for every billable service rendered. The focus is on itemizing each component of care accurately to ensure that providers receive appropriate compensation for their efforts.

In contrast, Value-Based Care shifts the focus from quantity to quality. Instead of rewarding the number of services provided, VBC models tie reimbursement to patient outcomes and overall health improvements. This paradigm shift necessitates changes in how medical coding and documentation are approached. Under VBC, documentation must reflect not only the services provided but also demonstrate the value delivered through improved patient outcomes and efficient resource utilization.

The transition from FFS to VBC has profound implications for medical coders and healthcare practitioners alike. In a value-based framework, documentation needs to be comprehensive yet focused on outcomes rather than merely listing procedures performed. Coders need to capture data that can illustrate improvements in patient health metrics or adherence to evidence-based guidelines. This requires a broader understanding of clinical pathways and potential long-term benefits associated with certain interventions.

Moreover, value-based models demand enhanced coordination among healthcare teams, which should be reflected in documentation practices. Accurate coding now requires an integrated view of patient care across various settings-from primary care offices to specialty clinics-to ensure continuity and efficiency in treatment plans.

While these changes present challenges, they also offer opportunities for innovation within both clinical practice and administrative processes. Technological advancements such as Electronic Health Records (EHRs) play a critical role here by facilitating seamless data sharing among providers while supporting more sophisticated analytics required under VBC models.

Overall, as healthcare continues its gradual shift towards Value-Based Care systems, the roles of medical coding and documentation evolve from being mere transactional records into strategic tools that drive quality improvement initiatives across entire organizations. Adapting to this transformation will be essential for healthcare providers aiming not only to remain financially viable but also committed stewards of better health outcomes for all patients they serve.

The transition from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based care (VBC) in medical coding represents a significant shift in the healthcare payment landscape. This evolution is driven by an overarching goal: to improve patient outcomes while controlling costs. However, as with any substantial change, it comes with its own set of challenges and benefits.

One of the primary challenges in moving from FFS to VBC is the fundamental rethinking of how healthcare providers are compensated. Under the traditional FFS model, providers are paid for each service or procedure they perform, which can inadvertently encourage volume over quality. This model often leads to unnecessary tests and procedures, inflating healthcare costs without necessarily improving patient health outcomes.

Transitioning to VBC requires a paradigm shift where providers are rewarded for the quality and efficiency of care rather than the quantity. This shift demands substantial changes in medical coding practices. Accurate and consistent coding becomes paramount because reimbursement under VBC models depends heavily on demonstrating value through clinical outcomes and overall patient health improvements. Coders must be retrained to understand new metrics and criteria that define value-based reimbursements, such as quality measures, patient satisfaction scores, and cost efficiency.

Moreover, implementing VBC requires significant investments in technology and infrastructure. Healthcare systems need advanced data analytics capabilities to track outcomes effectively, measure performance against benchmarks, and identify areas needing improvement. The initial setup can be costly and time-consuming, posing a barrier for smaller practices with limited resources.

Despite these challenges, transitioning to VBC offers substantial benefits that align with evolving healthcare priorities.

Furthermore, this approach fosters innovation in treatment methods as providers seek more effective ways of managing chronic diseases and preventive care strategies that can keep patients healthier longer-a win-win scenario that enhances both individual well-being and public health.

Financially, while the initial transition may require investment, VBC ultimately promotes cost savings by reducing unnecessary tests and hospital readmissions through better management of chronic conditions and preventative care initiatives. For payers like insurance companies or government programs such as Medicare/Medicaid, this means more sustainable healthcare spending over time.

In conclusion, while transitioning from fee-for-service to value-based care presents certain hurdles-chief among them being the need for new coding practices and technological upgrades-the potential benefits cannot be overstated. Improved patient outcomes coupled with reduced healthcare costs make this transition not only necessary but also highly beneficial for all stakeholders involved in the modern healthcare ecosystem. As we move forward into an era increasingly focused on accountability and excellence in medicine delivery systems worldwide will continue adapting their approaches towards achieving greater efficiencies through value-driven methodologies thereby creating healthier populations at lower expenses across global markets alike!

In the ever-evolving landscape of healthcare, payment models play a critical role in shaping the efficiency and effectiveness of medical practices. Two prominent models, Fee-for-Service (FFS) and Value-Based Care (VBC), have been at the forefront of discussions regarding their impact on various aspects of healthcare delivery, including medical coding efficiency. Through case studies, we can gain valuable insights into how these models influence coding processes and ultimately affect patient care.

Fee-for-Service is a traditional payment model where providers are reimbursed for each service or procedure performed. This model incentivizes volume over value, often leading to an increased number of services rendered without necessarily improving patient outcomes. In terms of medical coding, FFS can result in a high volume of claims requiring meticulous documentation and coding accuracy to ensure proper reimbursement. Case studies have shown that under FFS, coders often face immense pressure to process large quantities of codes swiftly, which can lead to burnout and potentially increase the risk of errors. However, this pressure also drives advancements in coding technologies and tools designed to handle high volumes efficiently.

Conversely, Value-Based Care shifts the focus from quantity to quality by aligning provider incentives with patient outcomes. This model rewards healthcare providers for delivering high-quality care and improving patient health rather than merely increasing service numbers. In terms of medical coding efficiency, VBC encourages a more streamlined approach. Coding becomes an integral part of assessing overall care quality rather than just billing purposes. Case studies indicate that under VBC, coders collaborate closely with clinical teams to ensure accurate representation of patient conditions and treatment plans in the codes used. This collaborative environment fosters a deeper understanding among coders about clinical terminology and practices, enhancing accuracy and reducing discrepancies.

Moreover, VBC incentivizes healthcare organizations to invest in integrated health information systems that facilitate seamless communication between various departments involved in patient care. Such systems improve data sharing across platforms, aiding coders with comprehensive access to necessary information for precise coding decisions. As a result, medical coding becomes not only more efficient but also more meaningful within the broader context of patient care management.

However, transitioning from FFS to VBC poses its own set of challenges. Organizations must navigate complex changes in workflows and adapt their existing infrastructure to support value-based initiatives effectively. Training programs are crucial during this transition phase as they equip coders with knowledge about new protocols required under VBC models while reinforcing best practices learned through years operating within FFS structures.

In conclusion, examining case studies highlighting different payment models provides invaluable insights into how these frameworks shape medical coding efficiency-an essential component influencing both operational success within healthcare organizations and quality outcomes experienced by patients themselves. While Fee-for-Service emphasizes productivity through volume-driven mechanisms often necessitating rapid processing speeds from coders amidst heavy workloads; Value-Based Care promotes collaboration among interdisciplinary teams focused on achieving superior clinical results supported by robust technological infrastructures facilitating accurate code assignments reflective true nature patients' conditions ultimately paving way toward sustainable future wherein improved efficiencies coexist harmoniously alongside enhanced levels compassionate caregiving across entire continuum modern medicine today!

The healthcare landscape is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the shift from fee-for-service to value-based care payment models. This evolution not only affects how healthcare services are paid for but also redefines the roles of various professionals within the industry. Among those most affected by this transition are medical coders, whose responsibilities are expanding and evolving in response to these changes.

Traditionally, medical coders have played a critical role in the fee-for-service model. Their primary responsibility was to accurately translate patient encounters into standardized codes that could then be used for billing purposes. The emphasis was on volume; more procedures meant more coding and ultimately more revenue. However, as the focus shifts toward value-based care, where providers are rewarded for quality rather than quantity, medical coders find themselves at the center of a paradigm shift.

In a value-based care environment, accurate coding remains essential but takes on a new dimension of importance. Coders must now ensure that the data they input accurately reflects patient outcomes and quality measures. This requires not only meticulous attention to detail but also an understanding of clinical nuances and quality indicators that were less emphasized in the fee-for-service era. Coders need to be adept at capturing data that supports evidence-based practices, quality metrics, and patient satisfaction scores-all elements that influence reimbursement under value-based models.

Moreover, as healthcare systems increasingly rely on sophisticated data analytics to drive decision-making and improve patient outcomes, medical coders are becoming integral members of multidisciplinary teams focused on delivering high-quality care efficiently. They are expected to collaborate with clinicians, administrators, and IT specialists to ensure that coding processes align with broader organizational goals related to quality improvement and cost reduction.

This evolving role necessitates ongoing education and training for medical coders. Familiarity with emerging technologies such as electronic health records (EHRs), artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning is becoming indispensable. These tools can enhance coding accuracy and efficiency but require new skills and competencies from coders who must remain agile in adapting to technological advancements.

Furthermore, medical coders must develop strong analytical skills to interpret complex datasets and contribute meaningfully to discussions about care delivery improvements. They play an essential role in identifying trends that can inform policy decisions or operational strategies aimed at maximizing value while minimizing costs.

In conclusion, as healthcare continues its shift towards value-based care payment models, the role of medical coders is being redefined from simple data processors to vital contributors in achieving high-quality patient outcomes. Their work now extends beyond transactional tasks into strategic functions that support organizational objectives in a rapidly changing environment. By embracing this expanded scope of responsibilities through continuous learning and collaboration across disciplines, medical coders will remain pivotal players in shaping the future of healthcare delivery systems worldwide.

|

|

This article or section may have been copied and pasted from another location, possibly in violation of Wikipedia's copyright policy. (June 2022)

|

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

|

A chart of accounts (COA) is a list of financial accounts and reference numbers, grouped into categories, such as assets, liabilities, equity, revenue and expenses, and used for recording transactions in the organization's general ledger. Accounts may be associated with an identifier (account number) and a caption or header and are coded by account type. In computerized accounting systems with computable quantity accounting, the accounts can have a quantity measure definition. Account numbers may consist of numerical, alphabetic, or alpha-numeric characters, although in many computerized environments, like the SIE format, only numerical identifiers are allowed. The structure and headings of accounts should assist in consistent posting of transactions. Each nominal ledger account is unique, which allows its ledger to be located. The accounts are typically arranged in the order of the customary appearance of accounts in the financial statements: balance sheet accounts followed by profit and loss accounts.

The charts of accounts can be picked from a standard chart of accounts, like the BAS in Sweden. In some countries, charts of accounts are defined by the accountant from a standard general layouts or as regulated by law. However, in most countries it is entirely up to each accountant to design the chart of accounts.

A chart of accounts is usually created for an organization by an accountant and available for use by the bookkeeper.

Each account in the chart of accounts is typically assigned a name. Accounts may also be assigned a unique account number by which the account can be identified. Account numbers may be structured to suit the needs of an organization, such as digit/s representing a division of the company, a department, the type of account, etc. The first digit might, for example, signify the type of account (asset, liability, etc.). In accounting software, using the account number may be a more rapid way to post to an account, and allows accounts to be presented in numeric order rather than alphabetic order.

Accounts are used in the generation of a trial balance, a list of the active general ledger accounts with their respective debit and credit balances used to test the completeness of a set of accounts: if the debit and credit totals match, the indication is that the accounts are being correctly maintained. However, a balanced trial balance does not guarantee that there are no errors in the individual ledger entries.

Accounts may be added to the chart of accounts as needed; they would not generally be removed, especially if any transaction had been posted to the account or if there is a non-zero balance.

While some countries define standard national charts of accounts (for example France and Germany) others such as the United States and United Kingdom do not. In the European Union, most countries codify a national GAAP (consistent with the EU accounting directives) and also require IFRS (as outlined by the IAS regulation) for public companies. The former often define a chart of accounts while the latter does not. The European Commission has spent a great deal of effort on administrative tax harmonisation, and this harmonization is the main focus of the latest version of the EU VAT directive, which aims to achieve better harmonization and support electronic trade documents, such as electronic invoices used in cross border trade, especially within the European Union Value Added Tax Area. However, since national GAAPs often serve as the basis for determining income tax, and since income tax law is reserved for the member states, no single uniform EU chart of accounts exists.

There are various types of accounts:[1]

A chart of accounts compatible with IFRS and US GAAP includes balance sheet (assets, liabilities and equity) and the profit and loss (revenue, expenses, gains and losses) classifications. If used by a consolidated or combined entity, it also includes separate classifications for intercompany transactions and balances.

Account Number—Account Title[3]—Balance: Debit (Dr) / Credit (Cr)

1.0.0 Assets (Dr)

2.0.0 Liabilities (Cr)

3.0.0 Equity (Cr)

4.0.0 Revenue (Cr)

5.0.0 Expenses (Dr)

6.0.0 Other (Non-Operating) Income And Expenses (Dr / Cr)

7.0.0 Intercompany And Related Party Accounts (Dr / Cr)

The French generally accepted accounting principles chart of accounts layout is used in France, Belgium, Spain and many francophone countries. The use of the French GAAP chart of accounts layout (but not the detailed accounts) is stated in French law.

In France, liabilities and equity are seen as negative assets and not account types in themselves, just balance accounts.

The Spanish generally accepted accounting principles chart of accounts layout is used in Spain. It is very similar to the French layout.

The complete Swedish BAS standard chart of about 1250 accounts is also available in English and German texts in a printed publication from the non-profit branch BAS organisation. BAS is a private organisation originally created by the Swedish industry and today owned by a set general interest groups like, several industry organisations, several government authorities (incl GAAP and the revenue service), the Church of Sweden, the audits and accountants organisation and SIE (file format) organisation, as close as consensus possibly (a Swedish way of working without legal demands).

The BAS chart use is not legally required in Sweden. However, it is politically anchored and so well developed that it is commonly used.

The BAS chart is not an SIS national standard because SIS is organised on pay documentation and nobody in the computer world are paying for standard documents[citation needed]. BAS were SIS standard but left. SIS Swedish Standards Institute is the Swedish domestic member of ISO. This is not a government procurement problem due to the fact all significant governmental authorities are significant members/part owners of BAS.

An almost identical chart of accounts is used in Norway.

Overhead may be: